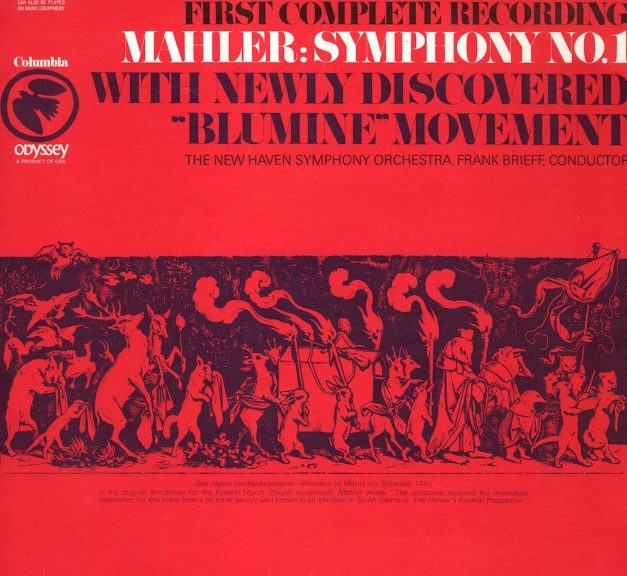

LP Art: Mahler’s Blumine

MAHLER: SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN D MAJOR

With Newly Discovered “Blumine” Movement (From the Version of 1893)

The New Haven Symphony Orchestra Frank Brieff, Conductor

Columbia Odyssey 32 16 0286

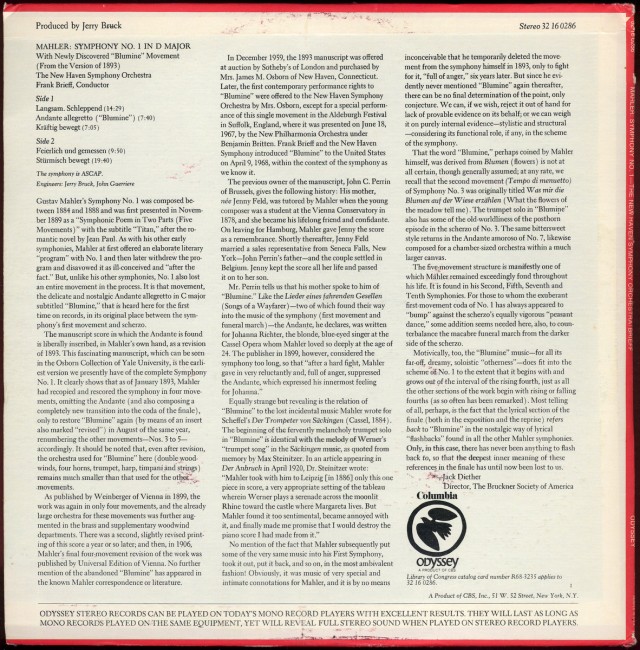

Side 1

Langsam. Schleppend (14:29)

Andante allegretto (“Blumine”) (7:40)

Kraftig bewegt (7:05)

Side 2

Feierlich und gemessen (9:50)

Stiirmisch bewegt (19:40)

The symphony is ASCAP.

Engineers: Jerry Bruck, John Guerriere

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 was composed between 1884 and 1888 and was first presented in November 1889 as a “Symphonic Poem in Two Parts (Five Movements) ” with the subtitle “Titan,” after the romantic novel by Jean Paul. As with his other early symphonies, Mahler at first offered an elaborate literary “program” with No. 1 and then later withdrew the program and disavowed it as ill-conceived and “after the fact.” But, unlike his other symphonies. No. 1 also lost an entire movement in the process. It is that movement, the delicate and nostalgic Andante allegretto in C major subtitled “Blumine,” that is heard here for the first time on records, in its original place between the symphony’s first movement and scherzo.

The manuscript score in which the Andante is found is liberally inscribed, in Mahler’s own hand, as a revision of 1893. This fascinating manuscript, which can be seen in the Osborn Collection of Yale University, is the earliest version we presently have of the complete Symphony No. 1. It clearly shows that as of January 1893, Mahler had recopied and rescored the symphony in four movements, omitting the Andante (and also composing a completely new transition into the coda of the finale), only to restore “Blumine” again (by means of an insert also marked “revised”) in August of the same year, renumbering the other movements—Nos. 3 to 5— accordingly. It should be noted that, even after revision, the orchestra used for “Blumine” here (double woodwinds, four horns, trumpet, harp, timpani and strings) remains much smaller than that used for the othesc’v movements.

As published by Weinberger of Vienna in 1899, the work was again in only four movements, and the already large orchestra for these movements was further augmented in the brass and supplementary woodwind departments. There was a second, slightly revised printing of this score a year or so later; and then, in 1906, Mahler’s final four-jnovement revision of the work was published by Universal Edition of Vienna. No further mention of the abandoned “Blumine” has appeared in the known Mahler correspondence or literature.

In December 1959, the 1893 manuscript was offered at auction by Sotheby’s of London and purchased by Mrs. James M. Osborn of New Haven, Connecticut. Later, the first contemporary performance rights to “Blumine” were offered to the New Haven Symphony Orchestra by Mrs. Osborn, except for a special performance of this single movement in the Aldeburgh Festival in Suffolk, England, where it was presented on June 18, 1967, by the New Philharmonia Orchestra under Benjamin Britten. Frank Brieff and the New Haven Symphony introduced “Blumine” to the United States on April 9,1968, within the context of the symphony as we know it.

The previous owner of the manuscript, John C. Perrin of Brussels, gives the following history: His mother, nee Jenny Feld, was tutored by Mahler when the young composer was a student at the Vienna Conservatory in 1878, and she became his lifelong friend and confidante. On leaving for Hamburg, Mahler gave Jenny the score as a remembrance. Shortly thereafter, Jenny Feld married a sales representative from Seneca Falls, New York—John Perrin’s father—and the couple settled in Belgium. Jenny kept the score all her life and passed it on to her son.

Mr. Perrin tells us that his mother spoke to him of “Blumine.” Like the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer)—two of which found their way into the music of the symphony (first movement and funeral march)—the Andante, he declares, was written for Johanna Richter, the blonde, blue-eyed singer at the Cassel Opera whom Mahler loved so deeply at the age of 24. The publisher in 1899, however, considered the symphony too long, so that “after a hard fight, Mahler gave in very reluctantly and, full of anger, suppressed the Andante, which expressed his innermost feeling for Johanna.”

Equally strange but revealing is the relation of “Blumine” to the lost incidental music Mahler wrote for Scheffel’s Der Trompeter von Sdckingen (Cassel, 1884). The beginning of the fervently melancholy trumpet solo in “Blumine” is identical with the melody of Werner’s “trumpet song” in the Sdckingen music, as quoted from memory by Max Steinitzer. In an article appearing in Der Anbruch in April 1920, Dr. Steinitzer wrote: “Mahler took with him to Leipzig [in 1886] only this one piece in score, a very appropriate setting of the tableau wherein Werner plays a serenade across the moonlit Rhine toward the castle where Margareta lives. But Mahler found it too sentimental, became annoyed with it, and finally made me promise that I would destroy the piano score I had made from it.”

No mention of the fact that Mahler subsequently put some of the very same music into his First Symphony, took it out, put it back, and so on, in the most ambivalent fashion! Obviously, it was music of very special and intimate connotations for Mahler, and it is by no means

inconceivable that he temporarily deleted the movement from the symphony himself in 1893, only to fight for it, “full of anger,” six years later. But since he evidently never mentioned “Blumine” again thereafter, there can be no final determination of the point, only conjecture. We can, if we wish, reject it out of hand for lack of provable evidence on its behalf; or we can weigh it on purely internal evidence—stylistic and structural —considering its functional role, if any, in the scheme of the symphony.

That the word “Blumine,” perhaps coined by Mahler himself, was derived from Blumen (flowers) is not at all certain, though generally assumed; at any rate, we recall that the second movement (Tempo di menuetto) of Symphony No. 3 was originally titled Was mir die Blumen auf der Wiese erzdhlen (What the flowers of the meadow tell me). The trumpet solo in “Blumine” also has some of the old-worldliness of the posthorn episode in the scherzo of No. 3. The same bittersweet style returns in the Andante amoroso of No. 7, likewise composed for a chamber-sized orchestra within a much larger canvas.

The five-movement structure is manifestly one of which Mahler remained exceedingly fond throughout his life. It is found in his Second, Fifth, Seventh and Tenth Symphonies. For those to whom the exuberant first-movement coda of No. 1 has always appeared to “bump” against the scherzo’s equally vigorous “peasant dance,” some addition seems needed here, also, to counterbalance the macabre funeral march from the darker side of the scherzo.

Motivically, too, the “Blumine” music—for all its far-off, dreamy, soloistic “otherness”—does fit into the scheme of No. 1 to the extent that it begins with and grows out of the interval of the rising fourth, just as all the other sections of the work begin with rising or falling fourths (as so often has been remarked). Most telling of all, perhaps, is the fact that the lyrical section of the finale (both in the exposition and the reprise) refers back to “Blumine” in the nostalgic way of lyrical “flashbacks” found in all the other Mahler symphonies. Only, in this case, there has never been anything to flash back to, so that the deepest inner meaning of these references in the finale has until now been lost to us.

Jack Diether

Director, The Bruckner Society of America

One thought on “LP Art: Mahler’s Blumine”

I have this. Columbia radio station service album I picked up at a thrift store. Looks to be the same. Nice.