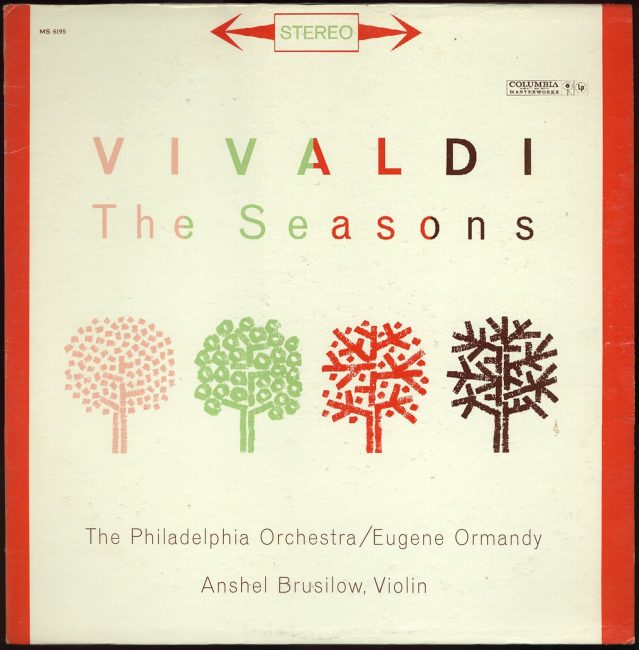

LP Art: Vivaldi by Ormandy

Vivaldi: The Four Season

Eugene Ormandy / Philadelphia Orchestra

Anshel Brusilow: Violin

Columbia Masterworks MS 6195

The difference between seventeenth and eighteenth century program music and nineteenth and twentieth century program music goes beyond matters of style. There is a philosophical difference. Sometime early in the nineteenth century—probably when Beethoven wrote his Pastoral Symphony-musicians began to feel that their art could not and should not attempt to express ideas and images without the aid of texts. Purely instrumental music moved in the realms of the abstract; it might suggest, to be sure, but only the vaguest sorts of things. So we find Beethoven rather snobbishly admonishing his auditors to hear in the Pastoral Symphony “an expression of feeling rather than depiction,” although the cuckoo sounds his two notes with unmistakable insistence, the brook runs gurgling by and the thunderstorm is chronicled in the most painstaking detail, from its first ominous rumors to its last faint retorts. For the romantic age and even more for our vauntedly anti-romantic one, the task of “mere depiction” was relegated to the lesser artist or the artisan. In painting, laborious portraiture and landscapes gave place to the grand sweep of Delacroix which gave place to the grand vagueness of Cezanne which gave place to the grand dribbles of Jackson Pollock. So in music men who were born “depicters,” whose response to the world was immediate and physical, were obliged to trim in their exuberance and pretend that what they had to say lay too deep for words. Liszt gave his tone-poems titles like That Which Is Overheard Upon the Mountain, and Richard Strauss, after penning a delightful and completely accurate program for his Domestic Symphony, pusillanimously decided to suppress it.

Not so the eighteenth century. Bach’s Cantatas, Schweitzer and others have helped us to see, rest on a system of elaborately circumstantial word-painting, a system which he carried over, to some extent, into his instrumental compositions. Handel and Haydn are not far behind him as illuminators of the word. The harpsichord pieces of Rameau and Couperin are never designated merely Allegro or Moderato but The Trophy, or Sister Monica, or The Savages; even when (as frequently happened) their inspiration was musical and musical only, both composers took good care to invent an a posteriori title and satisfy their public.

Antonio Vivaldi, no less than his French and German contemporaries, was of a story-telling turn of mind. A not inconsiderable number of his 454 concertos have titles to them, and doubtlessly the names of many more are either lost or were never written down. The twelve concertos of Opus 8—from which The Seasons are drawn—were published in Amsterdam around 1725, under the peculiar title, The Conflict Between Harmony and Invention. Apparently Vivaldi meant to indicate thus the intransigence of “harmony” or music when “invention” or the imaginative faculty tries to impose extra-musical meanings upon it. Harmony wishes to be a simple F minor scale; Invention wishes that scale to “be” a man slipping on the ice. Significantly, seven of the concertos bear titles, five do not: Invention wins the conflict.

Few programmatic works have been more fully annotated by their composer than The Seasons. Not only is a descriptive sonnet attached to each of the concertos, but the pertinent lines from the sonnets are printed above the music that is meant to illustrate them. Vivaldi even goes further and labels certain “leitmotifs” specifically “mosche e mosconi” (“gnats and flies”) or “il cane che grida” (“the barking dog”), etc. With such formidable documentation it would be strange indeed if a composer of Vivaldi’s genius failed to paint the pictures he set himself. The Seasons was a great success all over Europe. Marc Pincherle quotes only one dissenting opinion in his Vivaldi, Genius of the Baroque, that of a chauvinistic Frenchman who, m 1754, insisted that the listener could always divine what a French musician wanted to portray whereas “in Vivaldi’s Primavera he finds only shepherd dances which are common to all seasons, and where consequently spring is no more represented than summer or fall.”

One of the most remarkable things about these genre paintings is that they are achieved by the simplest means—they are watercolors rather than oils. Vivaldi was a kind of early eighteenth-century Rimsky-Kor’sakov: he had at his command a richer orchestral palette than all but a few of his contemporaries. And yet he chose nothing but string tone for The Seasons: no horns for the hunt, no oboe for the cuckoo, no brass for the barking dog or flute for the wafting zephyr. Furthermore, Vivaldi remains scrupulously faithful to the form of the baroque violin concerto, whose ritornellos and episodes are far from ideally designed for the purpose of consecutive narrative. These are limitations which he not only triumphs over but turns to good account, pitting the solo violinist against the full body of strings in all sorts of ingenious ways.

LA PRIMAVERA (SPRING)

I. Allegro. Spring has come and, rejoicing, the birds greet it with happy song. The streams softly murmur to the wafting of gentle breezes. But the sky suddenly grows black; lightning and thunder speak out. Peace is restored and the little birds continue their sweet singing.(Vivaldi requires three solo violins to imitate the bird songs.)

II. Largo. Here in the pleasant, flowering mead, the goatherd slumbers, lulled by the rustling leaves, his faithful dog by his side.

(Written in four parts only, the solo violin represents the sleeping goatherd, the first and second violins the rustling leaves, and the violas the dog, barking two notes to the measure.)

III. Allegro. Nymphs and shepherds dance to the festive sound of a rustic musette under the bright sky of spring.

(A slanting siciliano.)

L’ESTATE (SUMMER)

I. Allegro non molto; Allegro. Man, sheep, and tree droop under the mid-day sun of the pitiless season. The cuckoo unleashes its note, and soon the songs of turtledove and goldfinch are heard.

Soft zephyrs fan the air, but a querulous north wind usurps their place. The shepherd, alarmed by the rough blustering, weeps.

(Vivaldi does not convey the sense of enervating heat so vividly as does Haydn in the tenor cavatina “Distressful Nature Fainting Sinks” from the oratorio The Seasons: but given his smaller scope, the rendering is remarkable.)

II. Adagio. His weary limbs can find rest neither from fearful lightning and thunder nor from the angry swarms of gnats and flies.

(The shepherd’s plaint, begun toward the end of the first movement, continues in the Adagio, accompanied by the buzz of insects and the rumble of thunder.)

III. Presto. Ah! His fears are only too prophetic: storm and pelting hail cut down the growing sheaves of wheat.

(Storm music, already several times heard, is given the full treatment here; even the solo violin suggests strong agitation. The string writing could not be more idiomatic.)

L’AUTUNNO (AUTUMN)

I. Allegro. The peasant celebrates the happy harvest-time with dances and songs. Many, warmed by the wine of Bacchus, end their merry-making with slumber.

(Peasants dance an equitable dance to one of Vivaldi’s more memorable tunes. The soloist turns in a fine impersonation of a drunkard, truculent at first and making vain attempts to be dignified, but at last succumbing to sleep.)

II. Adagio molto. Everyone leaves off dancing and singing. The mild air is pleasing. This is the season that invites all alike to slumber to their heart’s content.

(Simple, non-melodic sequences on muted strings. Vivaldi directs the cembalist to perform arpeggios ad libitum.)

III. Allegro. At break of day the hunters go forth with horns, weapons and hounds: their prey flees and they follow his tracks. The beast, terrified by the sound of guns and hounds, endangered by his wounds, seeks to escape, but is overcome and dies.

(Strings suggest the sound of horns in fourths and thirds. The versatile soloist portrays the hunted animal with some pathos. Its efforts to escape are always foiled by the bland, well-satisfied hunting melody.)

L’INVERNO (WINTER)

I. Allegro non molto. To tremble, frozen amidst the icy snow; to breathe the sharp and wild wind; to run, stamping one’s feet for warmth; to have the teeth set achatter by all-conquering cold …

(Each proposition is treated in its turn. The point where the solo violin’s teeth chatter, thirty-two notes to the measure is unmistakable.)

II. Largo. To pass one’s days quietly and contentedly by the fireside while the rain without soaks all passers-by …

(The very cozy melody is accompanied by pizzicato strings, which attempt to suggest the rainstorm outside—as heard by one toasting his feet by the fire.)

III. Allegro. To walk on the ice, stepping slowly and peering carefully from side to side for fear of falling; to twirl about gaily, to slide, to fall down; to get up again and run across the ice so fearlessly that the ice begins to rumble and crack; to hear Sirroco and Boreas and all the winds howling as in battle; this is winter, and it has its joys.

(The Venetian Vivaldi was a great traveler which perhaps explains the accuracy of his description of the terrors and joys of winter, matters he could have learned little about from the choirmaster’s loft of the Ospedale della Pieta)

-DAVID JOHNSON

Anshel Brusilow, the 31 year old concertmaster of The Philadelphia Orchestra, is a native of Philadelphia. He studied at the Curtis Institute under Efrem Zimbalist and was later a scholarship student at the Philadelphia Musical Academy. Brusilow, who has been described by Eugene Ormandy as “one of the outstanding younger violinists,” was concertmaster of The Cleveland Orchestra before assuming his present role in September, 1959.

In the years following its first concert on November 16, 1900, The Philadelphia Orchestra has become one of the world’s leading artistic institutions. No other major symphony orchestra in the world plays more concerts or travels more miles during its average season. And everywhere that they are heard, Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphians make new friends. As one listener wrote after a nationwide telecast, “I can’t imagine heaven without The Philadelphia Orchestra.”