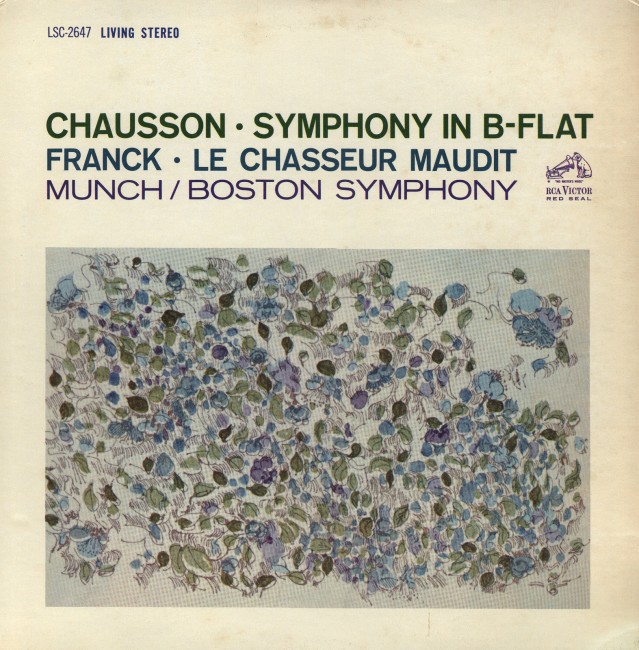

LP Art: Chausson and Munch

Chausson: Symphony in B-Flat

Franck: Le Chasseur Maudit

Munch / Boston Symphony

RCA Victor LSC-2647

LM/LSC-2647

Chausson Symphony in B-Flat

Franck Le Chasseur Maudit (The Wild Huntsman)

Charles Munch • Boston Symphony Orchestra

Produced by Richard Mohr Recording Engineer: Lewis Layton

It was in 1881 that a young man of twenty-six entered the class of Cesar Franck at the Paris Conservatoire. He had had a not too congenial teacher in Massenet. Franck, then fifty-nine and known as the organist at the Church of Sainte-Clotilde, was attracting young pupils to his side (d’Indy, Duparc, Ropartz, Pierne). His own attempts at composition were as yet almost unknown. Yet Franck at once inspired Ernest Chausson with hopes of becoming a composer.

These two were much alike. Chausson found in Franck a nature akin to his own, for each of these men was quite content to pursue his own musical dreams, create his own inner world of beauty without crying his wares in the market place. In the warmth of Franck’s sympathy and understanding, the poetry of Chausson’s style found its full florescence.

In spite of the difference in their ages, it so happened that these two composers did not find adequate performance until the very end of their lives, nor was there any general awareness of their qualities until after their deaths. Franck wrote his important works in the last decade of his life. His Symphony in D Minor was first performed in 1889, the year before his death. Chausson’s life was short; he was killed in a bicycle accident in 1899, at the age of forty-four. His Symphony in B-Flat (like Franck, he wrote only one) had been composed nine years before, but had its first just and revealing performance under Arthur Nikisch in Paris in 1897. When Chausson died two years later he was at the threshold of his full powers.

Critics, and sometimes friends, were inclined to dismiss his music as the work of an amateur for the sole reason that he happened to have independent means. Others were more ready to condemn “Franckisms” and “Wagnerisms” in his Symphony than to perceive its individuality, its distinctive personal qualities. Henri Gauthiers-Villars defended him: “Chausson’s friends were indignant or grieved according to their temperament, but he lost none of his amiability: ‘Pay no attention to these trifles. If my Symphony is good the critics will end sooner or later by acknowledging the fact.’ Chausson died at the moment when he had acquired the one quality that he lacked—self-confidence.” This was very like Franck who, after a doubtful first performance of his Symphony and its indifferent and mostly scornful reception, was quite content, even blissful, to have heard its actual sound.

Pierre de Breville wrote of Chausson’s style in the Mercure de France shortly after his death:

“It may be said that all his works exhale a dreamy sensitiveness which is peculiar to him. His music is saying constantly the word ‘c/ier.’ His passion is not fiery: it is always affectionate, and this affection is gentle agitation in discreet reserve. It is, indeed, he himself that is disclosed in it—a somewhat timid man, who shunned noisy expansiveness, and took joy in close relationships.”

Cesar Franck found the subject for Le Chasseur Maudit, his best-known symphonic poem, in 1883 when he came across the verse of a late eighteenth-century German poet, Gottfried August Biirger. Evidently in that country the enforcement of blue laws was obviated by the devil himself, always eager to claim his own. The following synopsis is printed in the score:

It was Sunday morning; in the distance there sounded the joyous ringing of bells and the religious chants of the crowd—Sacrilege! The savage Count of the Rhine has sounded his horn.

Hallo! Hallo! The hunt takes its course over grain fields, over meadow and moor . . . Stop, Count, I beg you. Listen to the pious singing—No!—Hallo! Hallo! —Stop, Count, I entreat you. Take care—No!—And the chase goes hurtling on its way like a whirlwind.

All of a sudden the Count finds himself alone; his horse is loath to go further; the Count blows into his horn, but it will not sound again … A voice dismal, implacable, curses him: ‘Sacrilegious man,’ it cries, ‘be hunted forever by hell itself!’

Then the flames leap up from all directions—the Count, seized by terror, flees, faster, always faster, pursued by a pack of demons … by daytime across abysses, at midnight through the air.

The four paragraphs of this argument are clearly discernible in the four sections of the score. The first seems to portray the peaceful Sunday landscape—horn fanfares alternate with a religious melody and the pealing of bells. In the next section the hunt is under way; in the third the curse is pronounced—by the awesome voice of the tuba; and in the fourth the chase becomes infernal, the pace growing faster and faster until the end.

Notes by John N. Burk